Easy to share link –> https://tinyurl.com/y9f2zwgr

Compiled by Faith Gibson, LM

Editor’s Note:

I’ve provided hard-copy references when available and URL info to easily link to on-line documentation. Reading historical source documents provides a fascinating insight that can’t be matched by the brief descriptions in this short history.

Whenever documents are available on-line, I have cited each paragraph individually, using sequential letters in parenthesis (a) (b), etc that correspond to the link.

However, I strongly suggest reading the entire document first, and then returning to follow and read the links.

Also note the links to other useful documents at the bottom of this rather long post!

FOREWORD:

Midwifery is the first organized healthcare discipline, with historical roots that trace back 5,000 years to ancient Egypt.

A healthcare discipline is one that protects, promotes and preserves health. Maternity care in particular is concerned with preserving, protecting and promoting the health of already healthy childbearing women. Historically midwives have provided maternity care as a supportive and non-medical process.

Obstetrics and gynecology is an allopathic surgical speciality that treats the pathologies of female reproduction relative to infertility, pregnancy, childbirth and tumors of female reproductive organs. Obstetricians are authorized to prescribe drugs, perform diagnostic procedures, medical treatments and perform surgery.

In the 20th century a bright-line distinction between the non-allopathic practice of midwifery and allopathic practice of medicine has developed. Midwives are not authorized to prescribe drugs or practice medicine, which was not a problem. Instead their role is to monitor the health of pregnant women and new mothers and assist them to maintain or improve their health status by providing information, advise and referral to medical services as needed.

A Short History of Midwifery in California: 1850 to 2014

A Short History of Midwifery in California: 1850 to 2014

On September 9th, 1850, when California became the 31st state in the Union, midwifery was a lawful but unregulated activity practiced by empirically-trained midwives.

The legacy practice of midwifery became an independent profession in 1917 after an amendment to the California Medical Practices Act (AB 1375) created a traditional or ‘non-nurse’ category of a state-certified midwife (a) (b). A licensing program was developed by the California Board of Medical Examiners (now called Medical Board of California) that required licentiates to have graduated from a Board-approved midwifery training program and to pass a state exam. The majority of state-certified midwives were Japanese-Americans who trained in one of the 27 professional midwifery schools in Japan ( c ).

Links (a) 1917 Sacramento Bee newspaper report of the Gebhart bill & legislative intro to AB 1375 (b) title page Medical Board’s Directory of Licentiates – 1918 (c} List of Medical Board-approved midwifery training programs

After 1917 the only exception to graduating from a midwifery training program was a “grandmother”

clause (a) that required practicing midwives to apply for a state license within 180 days. To qualify, they had to satisfactorily document equivalency in knowledge and skill, and provide letters of recommendation by two professionals willing to attest to their good character. The statute recommended that at least one reference be from a doctor familiar with the midwife’s practice and the second from her priest, minister or rabbi. (b)

Links (a) AB 1375’s grandmother clause; (b) List of midwives licensed under grandmother clause 1918-1929

During the next 32 years, 217 midwives (a) were licensed under AB 1375 to provide non-allopathic care as independent professionals (b). Over these three decades of public service only 3 midwives had their license revoked as reported in the Medical Board’s directory of its licentiates.

Links (a) Medical Board Directory of Licentiates, Summary – 1878 to 1950; 1949 memo ~ Gov. Earl Warren Office ~ mfry was independent profession under AB 1375

SB 966 ~Midwifery Suddenly on the Chopping Block

In spite of this impressive record, the midwifery-licensing program was suddenly dismantled in the summer of 1949 (a) by SB 966 at the request of the medical lobby and with the support of the Medical Board. This occurred without the prior knowledge of the midwifery profession.

Links (a) bill set for SB 966 – (a-1) MdBd Director Arnerich (a-2) Director Public Health (a-3) Attorney General

There was a perverse kind of symmetry in this unilateral action by the medical profession. It also occurred without the prior knowledge or participation of practicing midwives, just as the 1917 midwifery provision was passed before women had the right to vote. Article 24, which was the midwifery provision within AB 1375, stated the purpose for creating the category of state-certified midwives was: “providing the methods of citing said act, and … penalties for the violation thereof“.

While midwifery was an independent profession [see link for “memo from Gov Warren’s office” above], Article 24 gave the Medical Board the authority to prosecute midwives if they did anything the agency defined as an unauthorized practice of allopathic medicine.

In 1917, Article 24 of AB 1375 drew a bright line between “boy toys” (the use of drugs, surgery and ionizing radiation) and “girls toys” (non-allopathic management of normal childbirth). This gave the Board the right to revoke the license any midwife caught using ‘boy toys’.

SB 966 ~ Legislative sabotage of Licensed Midwifery in 1949 by Medical Board and organized medicine

In 1949, SB 966 the medical community used its legislative authority to repeal the midwifery certificate, thus eliminating non-allopathic profession of midwifery and making it’s practice illegal.

(b) published version of SB 966 – repealed application for license & deleted the category of state-certified midwife

This decision was explained by the Director of the Medical Board, James Arnerich, in his July 1, 1949 letter. He said midwifery was “almost a dead class”, as only two applications for licensure had been received in the previous years [see above link for “bill set for SB 966, ref #1”].

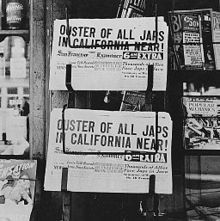

It should, however, be pointed out that the majority of professional midwives in California were of Japanese descent, and the time period under discussion was shortly after WWII. Just months after the US declared war on Japan, all Japanese-American citizens were ordered into internment camps by FDR’s Executive Order 9066. The Japanese population on the West Coast was relocated to Arkansas, Arizona, Hawaii, Utah, Wyoming, Canada and other locations including rural and desert areas of California.

It should, however, be pointed out that the majority of professional midwives in California were of Japanese descent, and the time period under discussion was shortly after WWII. Just months after the US declared war on Japan, all Japanese-American citizens were ordered into internment camps by FDR’s Executive Order 9066. The Japanese population on the West Coast was relocated to Arkansas, Arizona, Hawaii, Utah, Wyoming, Canada and other locations including rural and desert areas of California.

Links (a) partial list of midwives in out-of-state internment camps 1942-45

A letter in the SB 966 bill set from the director of the Public Health noted that only 456 births (0.2%) in California were attended by midwives in 1946. Perhaps because internment camps were federal government facilities, the category of birth attendant (midwife, doctor) and place of birth (out-of-hospital) were not recorded by the Department of Public Health. [see link above for “bill set for SB 966, ref #2”]. Whatever the reason, almost no midwife-attended births were registered in California during and following WWII.

As for new mfry applications, the Medical Board never approved any midwifery training programs in the state of California after passage of AB 1375 in 1917. The Board did, however, note that medical school graduates could qualify for midwifery licensure. However, the graduates of 58 midwifery programs worldwide (seven other states, and six foreign countries, including three in the USSR) were approved for licensure in California. It’s just that none of these many training programs had campuses in California.

After having been interned during WWII and cut-off from the 27 midwifery training programs in post-war Japan, there was no reasonable access to midwifery training for the vast majority of Californians. The equation is simple — without schools, no new graduates, without new graduates, no new midwifery applications. [see above link for “Medical Board-approved midwifery training programs”]

Hostility against Japanese-American citizens immediately after WWII may have played a part in the decision to eliminate midwifery. But the more important sociological influence was simply the end of the war and the need to create jobs for returning doctors. Thousands of physicians were released from their military service in 1946 and headed home to open new medical practices.

For the last two hundred years, the medical profession has officially recommended that doctors provide maternity care as the best ways to start a private practice, as women “tenderly delivered” could be counted on to recommend their doctor to family, friends, and neighbors. This personal referral network was doubly important for GPs who also provided medical services to men of all ages, children and older women.

For the last two hundred years, the medical profession has officially recommended that doctors provide maternity care as the best ways to start a private practice, as women “tenderly delivered” could be counted on to recommend their doctor to family, friends, and neighbors. This personal referral network was doubly important for GPs who also provided medical services to men of all ages, children and older women.

Just as “Rosie the Riveter” and the other women who ran the factories during the war suddenly found their jobs being given to returning soldiers, so “Martha the Midwife” and her colleagues were seen as taking jobs from doctors who were presumed to be more entitled and (of course) they had a family to support.

A little social engineering easily eliminated this problem by just leaving the last of the four categories of certificates in the Medical Practice Act off the list legally identifying those authorized to practice in California. Nothing in the legislative’s introductory description or the actual text of SB 966 pointed out that a legislative technicality had repealed the midwifery licensing law and summarily ended the professional of midwifery in California.

What is so clever about this legislative trick is that not a single word of it shows up on paper, and yet its absence is what makes the law change.

The final published version of SB 966 – repealing Article 9 (application for mfry license) & Article 3, Chapter 5, Division 2 (eliminated state-certified midwives from the list of MdBd licenses)

So “Midwifery Certificate” that was fourth on the list simply did not show up on the new list. As published in SB 966, there were only three licensing categories and midwifery was not one of them. While women had the right to vote in 1949, they had little political influence over the content of legislation and were no doubt to learn that midwifery was now “a deal class”.

Using this kind of ‘invisible ink” will show up again in the legislative history of midwifery in California.

The allopathic profession of obstetrics becomes the standard of care in the US

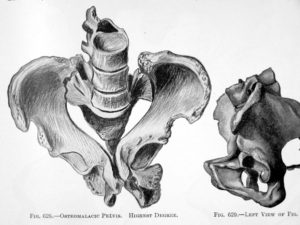

In the pre-antibiotic era (prior to the end of WWII), the American obstetrical profession concluded that childbirth in human females was a pathological process that routinely injured or even killed otherwise healthy childbearing women. It seemed that Mother Nature intended for women to be ‘used up’ in the process of giving birth, the way salmon die after spawning. Because childbirth so potentially dangerous, they believed that no amount of intervention was every too much.

To prevent these tragedies, many medical and surgical interventions were developed during the 19th and 20th centuries that could successfully treat potentially fatal complications. The next logical step for these interventions preemptively or ‘prophylactically’ during labor and birth in healthy women, in hopes of preventing or at least reducing the incidence of these complications. Doctors characterized pregnancy as a “nine-month disease that required a surgical cure”. From this perspective, the non-allopathic discipline of midwifery was seen as dangerously old-fashioned and totally irrelevant in the world of ‘modern’ medicine.

Laboring woman under influence of Twilight Sleep drugs (narcotics and the amnesic-hallucinogenic drugs scopolamine. Per hospital protocols, she is both hooded and a sheet is being used as a “straight jacket”

For those who could afford it, obstetrical management of labor under Twilight Sleep drugs and normal birth conducted as a sterile surgical procedure under general anesthesia was seen as the modern and much safer way to have a baby. This represents the

This represents the most profound change in childbirth practices in the history of the human species. Unfortunately, no one as yet realized that obstetrical interventions and invasive procedures used routinely on healthy childbearing women were themselves risky.

By the 1950s non-allopathic midwifery had indeed become a ‘dead class’ and was seamlessly replaced by obstetrics as the universal standard of care in the United States for all childbearing women.

Midwifery re-emerges as the allopathic discipline of Nurse-Midwifery

Programs for training registered nurses in a medicalized model of midwifery were seen as a time-saving device for obstetricians. State licensing of CNMs, who were seen as providing routine care in doctors’ offices and hospitals, would free up OB-GYN surgeons so they would attend to more complicated cases and perform more surgeries, Certified Nurse Midwives

Kate Bowland, CNM, pioneer in California midwifery, home birth provider for 45 years in Santa Cruz, Ca, one of our heroines

In 1974 a nurse-midwifery law was passed in California defining the CNM practice of midwifery as a medicalized discipline under the control of the medical profession in a category referred to by doctors as “physician extenders”. The formal ‘legislative intent’ for licensing RNs with advanced training in midwifery also enabled the newly created profession of nurse-midwifery to provide cost-effective maternity services (including care of the newborn) and well-woman GYN care to MediCal-eligible families, thus reducing the economic burden to the State.

In the role of physician extenders (also called ‘mid-level practitioners’), CNMs were required to practice under the supervision of an obstetrically-trained physician with hospital privileges. This was described as a “common sense” safety measure to provide an immediate “stepping stone” to physician consultation for non-urgent issues, and a seamless transfer of care whenever a client’s medical needs exceeded the CNM’s scope of practice. While the new category of nurse-midwives was legally required to practice under obstetrical supervision, the law did not require any California obstetrician to provide this legally-mandated service.

For the last four decades, California CNMs have only been able to practice with the cooperation and supervision of an obstetrician. Unfortunately, the obstetrical profession generally sees any independent practice of midwife as an economic threat, and so obstetricians are not as a rule very cooperative.

In addition, supervision of midwives is a legally-entangling arrangement that creates vicarious liability for the doctor. To protect their companies from such lawsuits, malpractice insurance carriers prohibit physicians from supervising any midwife who provides birth services unless it’s in a hospital L&D unit and is consistent with current standards of obstetrical medicine as an allopathic discipline.

From the standpoint of the obstetrical profession, the primary focus of nurse-midwifery was how its disincentives impacted obstetricians. They had a strong desire to eliminate economic competition from CNMs and avoid the perversely complicated relationship that enmeshed supervising physicians in liabilities issues and expensive malpractice premiums. What was supposed to be a safety net that provided a series of stepping stones to childbearing families in need of medicalized care turned into a stumbling block. A far more accurate description is a brick wall.

The supervision provision expected obstetricians to voluntarily take on unlimited vicarious liability for the midwife’s practice and do so without any economic compensation. Obviously, this was never going to work.

For the lucky few CNMs who could find a supervising physician (not many) their practice was restricted to protocols that met with the approval of medical malpractice carriers. This meant CNMs couldn’t offer any true “alternatives” to customary obstetrical practices. Last but not least, the expense associated with midwife-deliveries in the hospital was the same as vaginal delivery by obstetricians, so nurse-midwifery didn’t provide any cost-savings to the State’s MediCal program.

Background Maternal ~ Addendum #1 & 2 ~ {WORKS-N-PROGRESS}

Background Maternal ~ Addendum #1 & 2 ~ {WORKS-N-PROGRESS}

Statistical Facts about the Safety of Childbirth, part 1 ~ what everybody needs to know in order to make sense of the “midwife problem” and why would anyone seek out “alternatives” childbirth services when obstetrics appears to be the obviously safer and superior choice?

The Safe Childbirth Practice ~ the Difference btw Obstetrics & Physiologically-based Care, part 2

Attempts to Get Out of the Straight Jacket

of Physician-controlled Midwifery

In 1977 Governor Brown’s first administration described the impasse over mandatory physician supervision as “structural barriers to practice” which prevented nurse-midwives from providing services to low-income women and families seeking alternative care. The Department of Consumer Affairs, an agency under the executive branch of California government, actively supported passage of a new midwifery-licensing law as an independent discipline that was not controlled by the medical profession [AB 1896].

Link to the original and re-typed version of the 11-page document supporting AB 1896 by Deputy Director Michael Krisman, Sept 8, 1977

Link to the original and re-typed version of the 11-page document supporting AB 1896 by Deputy Director Michael Krisman, Sept 8, 1977

From 1977 to 1992 consumers, midwives, and at times the DCA, all energetically lobbied for a total of six midwifery licensing bills. However, there was endless, scathing and even vicious opposition by members of the obstetrical profession to each and every one. As a result, all efforts by midwives and mothers failed. Then in 1990, Senator Lucy Killea agreed to try again. Given her extraordinary background, she was the perfect person for the job.

During WWII Senator Killea had been an ‘operative’ (i.e. spy) for US Army Intelligence while stationed in Europe. In 1947 she and her husband Jack Killea were two of first three people hired by President Truman to run the brand new Central Intelligence Agency. As a member of the California Legislature, Senator Killea consistently supported women’s reproductive rights, which made her a target for political retribution. As a result, she became the first Roman Catholic in the US to be excommunicated by her parish for her legislative voting record.

Senator Lucy Killea ~ an American politician who served in the OSS, CIA & Cal Senate … died on January 18, 2017, in San Diego, at the age of 94.

Link NEWS UNDER THE RADAR – March 9, 2011; Lucy Killea’s CIA Network; Matt Potter alleges illegal evidence gathered by CIA operative Jack Killea

Bitter-Sweet Success ~ the Licensed Midwifery Practice Act of 1993

After 3 years of tireless effort by Senator Killea, midwives and grass-roots activists, the Licensed Midwifery Practice Act (SB 350) was passed in 1993. Its educational requirements and scope of practice were specifically developed to be ‘equivalent but not identical to nurse-midwifery’. But again vehement opposition by the medical lobby resulted in the same deal with the devil – the LMPA was burdened with the impossible definition of midwifery in the 1974 CNM law – a medicalized discipline under the control of the medical profession. The legal issue of physician supervision was another matter. It was a real and immediate problem that created a 20-year stand-off between midwives and organized medicine.

The first skirmish began with seven, day-long meetings of the “Midwifery Implementation Committee” held from March of 1994 to September of 1995 at the MBC Sacramento office. The meetings were chaired by Dr. Thomas Joas, an anesthesiologist and seated member of the governing board. In addition to midwives, the other “interested parties” were the California Medical Association (CMA) and the California Association of Professional Liability Insurers (CAPPLI).

The first skirmish began with seven, day-long meetings of the “Midwifery Implementation Committee” held from March of 1994 to September of 1995 at the MBC Sacramento office. The meetings were chaired by Dr. Thomas Joas, an anesthesiologist and seated member of the governing board. In addition to midwives, the other “interested parties” were the California Medical Association (CMA) and the California Association of Professional Liability Insurers (CAPPLI).

I wish I could say we devoted those 50 hours over 18 months identifying the characteristics of midwifery as a non-allopathic discipline and how that made it distinct from the allopathic specialty of obstetrics. Another good choice would have been developing a first-class standard of care for the community-based practice of midwifery. Or we could have worked out reliable methods of communication between the new profession of licensed midwifery and the Medical Board. The favorite on my wish list would have been a method to provide the Medical Board with statistical information about the clinical practice of midwifery by tracking the overall performance and safety of midwifery care provided by its new licentiates.

But alas we spend 50 grueling and exhausting hours arguing over tiny little every aspect of physician supervision while ignoring virtually every other aspect of the practice of licensed midwifery!

Twenty years later this is amusing to remember, but it was no fun at the time. In addition to the boredom of obsessive conversations about supervision, nothing we did during those 50 hours that supported, promoted or advanced the professionalism of California licensed midwifery. It was all about supervision, all the time, with every real and imagined aspect put under the microscope and discussed ad nauseum.

Most of the Committee’s time was focused on how the allopathic obstetrical profession could define ‘supervisory relationship’ to its economic advantage by controlling the non-nurse, non-allopathic discipline of midwifery. Of equal concern was protecting obstetricians from vicarious liability. This was in part accomplished by insisting that any obstetrician who had a professional ‘association’ with a home birth midwife would automatically lose their med-mal coverage.

At this point, Judge Cologne (former attorney with the anti-trust division of the Justice Department and current lobbyist for CAPPLI) reiterated the favorite solution or organized medicine: licensed midwives should just limit themselves to ‘performing’ hospital deliveries just like nurse-midwives, and all would be well!

When midwives pointed out that supervision didn’t work for CNMs who were providing hospital-based services, and certainly wouldn’t work for us since we were only providing care for planned home births, the conversation would inevitably turn to “clean-up legislation“. Committee chair Dr. Joas spent considerable time emphasizing the need for clean-up legislation and that it was up to us as midwives to take these problems back to the Legislature to broker a legislative ‘remedy’.

I tape-recorded 3 of the 7 meetings and transcribed several of the tapes. Had LMs gone to court to get the ‘supervision provision’ judicially set aside, these written transcripts all by themselves would have made our case.

Here are links to the transcripts:

Links: MBC-Midwifery Implementation Committee, Meeting #3, June 6, 1994 Tape 1 {Dr. Shelly Sella}, Tape 2 {Senator Killea}, Tape 3 {Juudge Cologne}; Meeting #6– September 94 {Nancy Chavez, Anitia Scuri}

There was, however, one aspect of this 50-hour marathon that produced a concrete result, albeit not a helpful one. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists convinced the MBC to pass regulations requiring each LM to have a written supervisory agreement with an obstetrician [see August 11, 1994, letter from ACOG to the MBC and OB-Gyn News September 15, 1993]. Based on the terms of these written agreements, each supervising physician would have ultimate authority, responsibility, and liability for the midwife’s practice.

There was, however, one aspect of this 50-hour marathon that produced a concrete result, albeit not a helpful one. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists convinced the MBC to pass regulations requiring each LM to have a written supervisory agreement with an obstetrician [see August 11, 1994, letter from ACOG to the MBC and OB-Gyn News September 15, 1993]. Based on the terms of these written agreements, each supervising physician would have ultimate authority, responsibility, and liability for the midwife’s practice.

ACOG president Dr. Vivian Dickerson provided their wish list to the Board in her 08-11-1994 letter. The Board believed that obstetricians were obviously the experts in childbirth and logically should set the regulatory rules for midwifery practice. As a result, ACOG’s letter became the template used by the Board for the proposed regulation.

When comparing ACOG’s letter and Section 2507 of the LMPA, one finds NO instances of the words “written practice guidelines” in the LMPA, while the August 1994 letter and the proposed regulation both contained four. When ACOG’s letter was laid side-by-side and compared line-by-line to the proposed regulation, 55 out of the 120 words in the letter also appear in the proposed text of 1379.21, using exactly the same placement, vocabulary, syntax and word order — in other words, a cut-and-paste job.

Luckily the ending of this story is anti-climactic. The regulatory hearing for 1379.21 was held November 1994 and submitted to the OAL in October 1995 (OAL File 95-1012-09S). Fortunately for mothers and midwives, the regulation was disapproved by the OAL on grounds of “clarity” and “necessity” in December 1995, again in May 1996 and the last time in 1997. At that point, the MBC declined to pursue the matter any further.

Ninja midwives give ACOG a run for its money!

Ninja midwives give ACOG a run for its money!

Despite this temporary setback, organized medicine continued to vigorously pursue the enforcement of physician supervision. However, licensed midwives just as vigorously insisted that the supervision provision had already proven itself to be a failed system relative to the practice of midwifery as a non-allopathic profession [see above link to DCA 1977 letter].

Given this history, the medical lobby’s imposition of a system demonstrably proven to be unworkable was a ‘disguised restriction’ on the professional services authorized under the LMPA. In addition to violating anti-competitive state laws, this was also illegal under the North American Trade Agreement.

NAFTA’s objective in relation to licensing is to prevent licensing requirements from being “unnecessary barriers to trade”, stating that state licensing requirements must:

“not constitute a disguised restriction of the provision of services ….. Requirements should be based on competence”.

In September 1992, California DCA memo to all its executive officers and bureau chiefs conveyed a request by Governor’s Trade Representative to each state agency to prepare a plan to implement NAFTA. As a measure of the “anti-competitive impact” on licensed professionals, the memo suggested the following questions:

(a) Are any of your licensing or certification statutes, regulations or procedures not based on objective and transparent criteria such as competence and the ability to provide the service?

(b) Are any of your licensing or certification statutes, regulations or procedures more burdensome than necessary to ensure the quality of the service?

(c) Are any of you licensing or certification statutes, regulations or procedures in themselves a restriction on the supply of the service?

These views were reiterated in a letter dated 01-11-94 from the Federation of State Medical Boards by Dorothy Harwood, who noted that:

“State medical board licensing standards are not pre-empted”.

Judged by NAFTA’s standards of fairness, physician supervision of midwives — CNMs or LMS — is clearly a violation of the North American Trade Agreement. As an economic competitor, the mandatory supervision of midwives by obstetricians — — is quite clearly a disguised restriction of the provision of services.

Judged by NAFTA’s standards of fairness, physician supervision of midwives — CNMs or LMS — is clearly a violation of the North American Trade Agreement. As an economic competitor, the mandatory supervision of midwives by obstetricians — — is quite clearly a disguised restriction of the provision of services.

Supervisory statutes in the CNM and LM practice acts were not based on competency (*see clarifying note below) and were significantly more burdensome than necessary to ensure the quality of the service.

In addition is to the restraint of trade issue and unfair business practices, the law requiring midwives to be supervised by obstetricians does not require any obstetrician in California to provide this legally essentially services.

** Note: When a regulated healthcare provider’s training and scope of practice are not sufficient to competently provide health care services independently, relevant statues call for “close supervision“.

Close supervision is typically defined as requiring the physician to be physically present when care is being provided. If a problem of any kind arises, the physician simply steps in and takes over. Under these circumstances healthcare service by a lesser-trained, less technically educated subordinate is overseen by a more highly trained, more experienced practitioner in the same field, which is a sensible arrangement.

But in the case of midwives, competency-based close supervision was not required. While ACOG claimed that safety was the reason they insisted on the mandatory supervision of midwives, obstetrician-supervisors were not required to be present, or even on the premises, and thus could not provide any advanced medical service in an emergency, making this a pro forma arrangement rather than a safety-based one.

The only undeniable and consistent effect of the supervisory clause for CNMs and LMS was to legally create the medical malpractice nightmare of “vicarious liability“. As a result, all three California professional liability carriers could point to a clause in their contracts that excludes coverage for ‘vicarious’ liability. Letters form med-mal carrier made it plain that supervision of midwives by insured obstetricians was prohibited under any and all circumstances.

A letter from NorCal in May of 1999 went even further by cautioning obstetricians not to give any assistance or advise if a midwife called them in an emergency, stating as rationale the notion that: “the courts might interpreted this as legally constituting supervision” and going on to say their med-mal insurance would not cover them in that case. The letter again stated that the obstetrical group’s contract did not cover any vicarious liability associated with the supervision of midwives.

As could be predicted, the double whammy of mandated supervision prohibited by med-mal carriers effectively denied childbearing women access to non-obstetrical care providers, and prevented professional midwives from practicing legally, which was clearly an economic advantage for the obstetrical profession.

Help from a highly unlikely source

In 1998 licensed midwife Alison Osborn was prosecuted by the MBC for not having a physician supervisor. A 1999 decision by OAL in the Osborn case confirmed that mandatory obstetrical supervision of midwives was a dysfunctional system and therefore unenforceable. Judge Jaime Roman ruled that provisions of the LMPA cannot lawfully be used to make the practice of midwifery functionally illegal.

According to this legal theory, the Legislature’s intention in passing the LMPA was a binding directive to make non-medical midwifery care again available to childbearing women who needed or wanted a professional alternative to obstetrical services.

According to this legal theory, the Legislature’s intention in passing the LMPA was a binding directive to make non-medical midwifery care again available to childbearing women who needed or wanted a professional alternative to obstetrical services.

The legacy tradition of midwifery had already been an independent profession in California from 1917 to 1949 under Article 24, but its licensing provision was dismantled in 1949 at the request of the medical lobby. Passage of the LMPA demonstrated the Legislature’s intent 45 years later to restore access to midwifery as a modern-day, non-allopathic profession authorized to provide maternity services to essentially healthy women.

Judge Roman’s decision stated that any licensed midwife who had documented a workable plan for consulting, referring or transferring care to an obstetrician or the obstetrical unit of a hospital had fulfilled the “ambit” of this provision. While medical lobbying groups continued to be outraged over this ruling, they also never had a ‘cease and desist’ order served on the MBC for failing to prosecute hundred of midwives for openly practicing without supervision over a 20-year span of time.

In 2000 a bill that amended the LMPA for the first time was carried by Senator Liz Figueroa (SB 1479) at the request of licensed midwives. It reduced some of the legal burdens of the unworkable supervision provision by implementing aspects of the legal theory in Judge Roman’s 1999 decision.

The amendment required each planned home birth (PHB), client and midwife, to identify arrangements for medical consultation, referral or transfer of care during the prenatal, intrapartum and postpartum-neonatal period that were specific to that particular client. The form included the name of a physician who could be contacted and/or concurrent care (ex. Kaiser) and identified a geographically-accessible hospital that the mother or baby could be transferred to if necessary. These arrangements were to be memorialized in writing, signed by mother and midwife and become a permanent part of the client’s midwifery record.

In addition, SB 1479 (Senator Liz Figueroa) included a “Legislative Intent” section that acknowledged, as a matter of California state law, that childbirth was a normal aspect of biology and not a medical disease. It also identified physiological management — the supportive, non-interventive practices associated with the community-based midwifery — as a non-allopathic discipline that is clearly distinct from obstetrical practice.

The midwifery model of care includes:

-

- informed choice

-

- continuity of individualized care

-

- sensitivity to the emotional and spiritual aspects of childbearing

-

- monitoring the mother throughout the childbearing cycle including

her physical, psychological, and social well-being

- monitoring the mother throughout the childbearing cycle including

-

- providing individualized education, counseling, and prenatal care

-

- continuous hands-on assistance during labor and delivery

-

- postpartum support

-

- minimizing technological interventions

-

- identifying and referring women who require obstetrical attention

Furthermore, the “Intent” language in SB 1479 legislatively upheld the right of essentially healthy childbearing women to self-determination in choosing the manner and circumstance of normal childbirth. This was a ‘corrective’ response by the Legislature that addressed two issues in a 1976 California Supreme Court ruling.

Furthermore, the “Intent” language in SB 1479 legislatively upheld the right of essentially healthy childbearing women to self-determination in choosing the manner and circumstance of normal childbirth. This was a ‘corrective’ response by the Legislature that addressed two issues in a 1976 California Supreme Court ruling.

In a criminal case brought against three lay midwives in Santa Cruz County in 1973, the Bowland Court ruled against the defendants by stating that pregnancy and childbirth as defined by the Medical Practice Act was a medical condition, thus making midwifery an unauthorized (thus illegal) practice of medicine. Bowland further noted that a pregnant woman’s right to choose a non-physician birth attendant or alternative birth setting had never been legally established since the California Legislature “had never gone so far” as to acknowledge the right of women to control the “manner and circumstances” under which they gave birth.

SB 1479 corrected both those problems. As mentioned earlier, the “Intent” language identified childbirth as a ‘normal bodily function and not a medical condition’, and also established a woman’s right to choose alternative birth settings. It cited evidence-based studies on the relative safety of alternative birth settings published in California and other countries that supported planned home birth as a responsible choice for an essentially healthy population of childbearing women with normal pregnancies.

In 2002 another amendment to the LMPA – SB 1950 – was sponsored by licensed midwives and authored by Senator Liz Figueroa. It contained a regulatory process for creating a professional standard of care for the community-based practice of midwifery. This ultimately required the Medical Board to abide by a midwifery standard when judging the merits of a complaint against a midwife licentiate, instead of having the agency ask an obstetrical consultant’s opinion.

Achieving consensus between the MBC, ACOG and licensed midwives for ‘state of the art’ evidenced based practice was long and very difficult, but the Standard of Care for California Licensed Midwives (SCCLM) was finally completed, approved by the MBC September 15, 2005 and adopted by the OAL March 9th, 2006.

Achieving consensus between the MBC, ACOG and licensed midwives for ‘state of the art’ evidenced based practice was long and very difficult, but the Standard of Care for California Licensed Midwives (SCCLM) was finally completed, approved by the MBC September 15, 2005 and adopted by the OAL March 9th, 2006.

In 2004 midwives approached Senator Figueroa again and asked if she would be willing to carry yet another piece of legislation, this time to create a Midwifery Advisory Council and Licensed Midwives Annual Report (LMAR). It took two years to work out the details, but SB 1638 was signed into law in 2006.

While the MBC is the regulatory agency for the licensed practice of midwifery, there was no regular, 2-way communication between midwives and physician-run governing Board. SB 1638 created a Midwifery Advisory Council under the auspices of the MBC to provide a cooperative interface between the state agency, its governing Board, and its midwife licentiates.

The law specified that at least 50% of the Council’s members should be licensed midwives, while the remaining portion should be consumers with “an interest in midwifery”. Apart from identifying the categories of public and professional members and specifying the ratio, SB 1638 otherwise left the Advisory Council’s configuration to the discretion of the MBC.

The Medical Board interpreted the word “consumer” as used in SB 1638 to indicate any citizen in California that was not a professionally licensed midwife. Obviously, obstetricians and Medical Board members are ‘not midwives’ and presumably have some general ‘interest’ in midwifery, so the Medical Board created a six-person council by appointing a member of its own governing Board, two ACOG-certified obstetricians, and three licensed midwives.

The three licensed midwives on the Midwifery Council — the author (Faith Gibson) Karen Ehrlich and Carrie Sparrevohn — objected to this overly-broad interpretation of ‘consumer’, which generally would be defined in this legal context as a non-professional who uses the professional service being regulated. The idea of obstetricians being appointed as “consumers” generated many contentious conversations and hard-feelings on both sides. Finally, in 2012 the Board agreed to replace one of its obstetrician-members with a consumer who actually had used the childbirth services of a licensed midwife.

Currently the MBC schedules three half-day Midwifery Advisory Council meetings a year.

The newly born Midwifery Advisory Council ~ more unexpected, but gratefully appreciated help

The newly born Midwifery Advisory Council ~ more unexpected, but gratefully appreciated help

One of the Midwifery Advisory Council’s first tasks was to implement the LMAR, which required the Council to create statistical reporting form many pages in length, along with a detailed manual for Ca LMs. Aside from an occasional complaint, the staff of the MBC had no information about the overall performance and safety of midwifery care as provided by its licentiates.

The development of the Midwifery Council as a politically effective advocate for midwifery was greatly aided by the MBC’s appointment of Barbara Yaroslavsky and Ruth Haskins to the Council.

At the time Barbara was already a seated member of the MBC ‘governing’ Board. Her position on the Midwifery Advisory Council was not the first time she had officially advocated for midwifery. As a Board member in 2005 she served on the MBC’s four-person “Midwifery Committee” chaired by Dr. Richard Fantozzi.

As a ‘consumer’ appointee (i.e. not a doctor), Barbara did not blindly promote the status quo. In the tradition of former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Barbara was not afraid to speak her mind on unpopular topics. In addition, she was refreshingly open-minded, midwife-friendly and a good listener who became a real ambassador for the midwifery profession.

The other crucial appointment to the Council was Dr. Ruth Haskins, a practicing obstetrician in the greater Sacramento area. As an ‘insider’ in the obstetrical community, Ruth’s appointment to the Council was critical in helping us negotiate between the many rocks and hard places erected by ACOG, CMA, and CAPPLI.

With Barbara and Ruth to provide their calm, no-nonsense attitude towards getting the job done, the first official project of the Mfry Council was the Licensed Midwives Annual Report. The LMAR required that we create a new web-based statistical system for reporting annual statistics that was to be run by the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD).

Each midwife is required to report the total number of clients served that year, the number who gave birth at home or in a birth center, those transferred to a hospital, reasons and outcomes for all clients regardless of the place of birth. This includes reporting significant morbidity and maternal or perinatal deaths, and the total number of normal spontaneous births and Cesarean sections.

Each midwife is required to report the total number of clients served that year, the number who gave birth at home or in a birth center, those transferred to a hospital, reasons and outcomes for all clients regardless of the place of birth. This includes reporting significant morbidity and maternal or perinatal deaths, and the total number of normal spontaneous births and Cesarean sections.

Links to website with document posted about the development of the LMAR

Statistical averages for the 10,668 clients served by LMs between 2010 and 2013 identified a spontaneous vaginal birth rate of 92%, hospital transfer rate of 19%, Cesarean section rate of 8% (nat’l average 32.8%), and a very low prematurity rate of 1% (nat’l average 12%). The neonatal mortality rate for LMs excluding lethal birth defects was 1.3 per 1,000 live births.

National birth certificate data linked to neonatal mortality don’t provide the mortality rate by category of the practitioner (MD, CNM, LM, EMTs, etc), or place-of-birth (hospital vs OOH). However, it does report neonatal mortality for term pregnancies (37+ weeks) and babies weighing over 5 ½ pounds. In 2012 (last year data available) that number, which includes birth defects, was a NMR of 2.2 per 1,000 live births.

Relief for mothers, midwives, and midwife-friendly obstetricians ~ the long overdue repeal of supervision

Over the 20-year span of the LMPA, three unsuccessful attempts were made to replace mandatory supervision with a functional relationship of collaboration between midwives and physicians (AB 1418, SB 1479 & SB 1950). But it was not until 2014 was the supervision provision finally repealed by AB 1368.

As a result of the new legislation, licensed midwifery is once again, technically speaking, an independent profession in California. But unlike the LMPA itself and its first 3 amendments sponsored by midwives, AB 1308 was sponsored by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). While AB 1308 repealed the supervision provision (for which we are all grateful), it also introduced new and far-reaching problems.

The Dysfunctional Practice of Midwifery under AB 1308

The Dysfunctional Practice of Midwifery under AB 1308

AB 1308 restricted the midwives’ scope of practice by dramatically expanding the category of healthy women that midwives are no longer authorized to provide childbirth services, or cannot do so without the prior approval of the obstetrical profession.

Since midwifery is a non-allopathic discipline, midwives have always transferred patients with symptoms of a complication requiring medical care to an MD or hospital obstetrical services. Midwives, physicians and the licensing statute (LMPA) all agree that this is as it should be.

There is also nearly unanimous agreement between midwives and physicians on what constitutes a serious “complication” requiring medical attention. As a result, there was no need for regulations to define the single word “complication” as used in the LMPA. For over 20 years, the clinical judgment of licensed midwives has proved more than sufficient.

But AB 1308 shifted the non-urgent category of women with a history of a prior complication or current non-urgent risk-factor into the same high-risk category as patients having a complication. The mere possibility of a future complication is being treated the same as a present-tense complication, in that AB 1308 requires the same immediate referral or transfer of care as a ‘complication’. It also applies the same criminal penalties for any perceived failure to refer or transfer. Politically-correct midwives politely describe this as ‘mission creep‘, others not so charitable simply call it a ‘land grab’.

The expanded involvement of the obstetrical profession as mandated by AB 1308 bars any pregnant woman with identified risk factors or medical conditions from making essential decisions about her own health care, even if she has legal or scientific grounds, or declines mandatory obstetrical evaluation for other reasons.

Midwives are not permitted to provide primary care (either prenatal or childbirth services) to such women unless the pregnant woman first agrees to be examined by an obstetrician and the doctor is willing to provide a formal medical opinion that the issue involved is not “likely to affect pregnancy or birth”.

If pregnant women object to or refuse to being medicalized, California LMs as a class are permanently enjoined from providing midwifery care.

AB 1308 also forbids to licensed midwives from caring for childbearing women who have post-dates pregnancies, even though this means dropping them from care without the mandated requirement that they be given two weeks notice to find a replacement provider. This includes breastfeeding mothers with lactational amenorrhea whose due dates are uncertain. It applies even if the mother-to-be is evaluated by an obstetrician and has sequential ultrasounds that confirmed normal levels of amniotic fluid and non-stressing testing (NST) that indicate normal fetal well-being.

Previously, all these categories were a specific part of the normal informed consent process outlined in Section V of the SCCLM:

Risk factors identified during the initial interview, or arising during the course of care: “Responsibility of the Licensed Midwife” and “Client’s Rights to Self-Determination”

Section V required midwives to advise clients with a history of previous medical conditions or non-urgent risk factors detected during their pregnancy to consult with a physician. However, the Standard of Care also acknowledged that childbearing women are mentally-competent adults. After being fully informed of all pertinent facts, they have the legal right to decline this advice as is true for any other competent adult.

When the SCCLM was being developed, ACOG’s Committee Opinions on “Informed Refusal (#166) and “Patient Autonomy: The Maternal-Fetal Relationship” (#214) was the model used to develop the legal language for Section V.

When the SCCLM was being developed, ACOG’s Committee Opinions on “Informed Refusal (#166) and “Patient Autonomy: The Maternal-Fetal Relationship” (#214) was the model used to develop the legal language for Section V.

Opinion #166 (Informed Refusal) notes:

Almost universally, informed consent laws have been liberalized … from the relatively paternalistic “professional or reasonable physician” standard to the “materiality of patient viewpoint” standard. … In the “patient viewpoint” standard, a physician must disclose … the risks and benefits that a reasonable person in the patient’s position would want to know in order to a make an “informed” decision.

ACOG Opinion #214 states that:

-

- … medical knowledge has limitations and medical judgment is fallible. Existing methods for detection … are not always reliable indicators of poor outcome, and there is often insufficient evidence for risk-determination or risk-benefit evaluation

-

- The role of the obstetrician should be one of an informed educator and counselor, weighing risks and benefits …. and realizing that tests, judgment and decisions are all fallible.

-

- Abiding by the patient’s autonomous decision will provide the best care for the pregnant woman and the fetus in most circumstances.

-

- In the event of an emergency … the obstetrician must respect the patient’s autonomy, continue to care for the pregnant woman, and not intervene against the patient’s wishes regardless of the consequences.

ACOG Committee Opinion #214 also identifies serious negative consequences when a patient’s autonomy is violated:

-

- A woman is wronged and may be harmed, whether physically, psychologically or spiritually.

-

- The patient’s subsequent loss of trust in the healthcare system may reduce the health care provider’s ability to help her and may deter others from seeking care.

-

- There may be other social costs associated with this violation of individual liberty.

Nothing I could say in support of the logic, rationality and practical necessity of respecting the autonomy of childbearing women could exceed, or even closely match ACOG’s very own published policies. But apparently, ACOG has an unpublished policy that restricts their noble principles to its own obstetrical patients, while not offering this same respect for autonomy to women being cared for by licensed midwives.

Return of the Dreaded Invisible Ink ~ legislative technicalities, circa 2013

AB 1308 employed a little-known legislative technicality to annul our standard of care (SCCLM) without our knowledge, permission or even an explanation. Midwives were shocked. The obstetrician negotiating for ACOG at one point said she was really impressed with its quality, so there was never any reason to suspect that our hard-fought-for standard of care was on the chopping block.

The idea of repealing or even changing our Standards was never mentioned during legislative negotiations between ACOG, AB 1308’s author, and midwives. Nothing in the bill’s many sequential drafts from February thru September, the legislature’s published synopsis of AB 1308’s important features, or the Medical Board’s final report on the practical effect of the newly passed bill made any statement about AB 1308 having eliminated the SCCLM.

However, the same ‘invisible ink‘ was used in in 1949 in Senate Bill 966, which eliminated the professional practice of midwifery by simply erasing the licensing category for state=certified midwives from the Medical Practices Act. This same strategy was used again in 2013 to make the SCCLM disappear. The critically informative language — in this case, the words “standard of care” and “repeal” — never appeared on paper during the legislative process and were not in the final version of AB 1308 signed into law by Governor Brown on October 9th, 2013. As a long-time supporter of midwifery, I think Governor Brown would be also be shocked learn that the bill he just signed was, in fact, a major step backward, as AB 1308 silently revoked the regulation that authorized the SCCLM.

California midwives didn’t even know that the SCCLM had been eliminated from the LMPA until three months later, when this was announced at the December 2013 Midwifery Council meeting. During that meeting, Curt Worden, MBC Chief of Licensing, offered to create a greatly redacted version of our Standards as an unofficial “practice guideline” for midwives. But he emphasized that as informal ‘guidelines’, they would have no legal force and could not be used to defend the practice of a licensed midwife in a disciplinary action. This is in stark contrast to the SCCLM, which required the Board to use a midwifery (i.e. not obstetrical) standard when judging the merits of a complaint.

California midwives didn’t even know that the SCCLM had been eliminated from the LMPA until three months later, when this was announced at the December 2013 Midwifery Council meeting. During that meeting, Curt Worden, MBC Chief of Licensing, offered to create a greatly redacted version of our Standards as an unofficial “practice guideline” for midwives. But he emphasized that as informal ‘guidelines’, they would have no legal force and could not be used to defend the practice of a licensed midwife in a disciplinary action. This is in stark contrast to the SCCLM, which required the Board to use a midwifery (i.e. not obstetrical) standard when judging the merits of a complaint.

The MBC’s unofficial version of these guidelines was published May 14th, 2014.

Link to the original SCCLM renamed “Practice Guidelines” with strike-thru revisions in red

Losing our midwifery Standard of Care is the single most detrimental aspect of AB 1308. Its repeal eliminated a pregnant woman’s right to self-determination, the midwife’s responsibility to advocate for and defend the decision-making autonomy of her clients, and the requirement that the MBC use midwifery standards when adjudicating charges against a midwife.

The decision to eliminate the SCCLM also dishonors the huge amount of work by the many people who so diligently to bring it to fruition, starting with passage of SB 1950 in 2002 by Senator Liz Figueroa and her highly committed office staff.

After SB 1950 was signed into law, the MBC staff and consultant Dr. Pat Chase labored for many months researching practice standards used in other jurisdictions. In particular, she was attempting to locate the most informative and comprehensive definition of “normal” as applied to pregnancy and childbirth.

In an MBC’s document called “Background Material” (October 8, 2004), Dr. Chase wrote: “All states define midwifery as the care for normal, low-risk pregnant women. The clearest definition [of normal] is from the California College of Midwives’ Standard of Care”.

In an MBC’s document called “Background Material” (October 8, 2004), Dr. Chase wrote: “All states define midwifery as the care for normal, low-risk pregnant women. The clearest definition [of normal] is from the California College of Midwives’ Standard of Care”.

The California licensed midwife provides maternity care to essentially healthy women who are experiencing a normal pregnancy.

An essentially healthy woman is without serious pre-existing medical or mental conditions affecting major body organs, biological systems or competent mental function. An essentially normal pregnancy is without serious medical conditions affecting either mother or fetus.”

As director of the California College of Midwives, I was honored to have its definition of ‘normal’ used in the final version of the SCCLM. Other source materials were drawn from the “international definition of a midwife” (ICM), state and national midwifery organizations, and standards-of-care published in seven other states, as well as the College of Midwives of British Columbia in Canada.

Once the Medical Board moved into the formulation phase of the SCCLM, licensed midwives, ACOG reps and Dr. Richard Fantozzi (Chair of the MBC’s Midwifery Committee, which included the very able Barbara Yaroslavsky, spent three long years (2003 to 2005) discussing every aspect of every concept and every word of the proposed standards.

In spite of being busy with his responsibilities as president of the MBC’s governing Board, Dr. Fantozzi was generous with his time, open-minded, and intellectually curious. He treated midwives with the utmost respect and the issues of midwifery practice with fairness. Best of all, he was fiercely protective whenever other physicians ridiculed midwives or attempted to use their power to disadvantage the midwifery program.

Dr. Ruth Haskins, an ACOG fellow who served on the organization’s internal midwifery committee, and ACOG attorney Shannon Smith-Crowley both contributed tremendously by being a conduit for ACOG’s concerns and objections, and helping all of us work out compromises that were mutually acceptable to midwives and the Medical Board.

Members of the MBC staff also ‘midwifed’ our project, including helpful legal advice from the Board’s senior counsel, Anita Scuri, and administrative support by Ron Joseph, the agency’s executive director until 2004. Legislative analyst Linda Whitney and Dave Thornton, the new executive director, patiently provide additional support, encouragement and helpful feedback.

Cheryl Thomson and Pat Thomas worked together to develop the formatting, research spelling of midwifery vocabulary and type the final document so it could be posted on the MBC website. The result of these thousands of hours of effort by more than a dozen people employed in two branches of California government was a first-class Standard of Care that mirrored other standards of high quality used worldwide by professional midwives.

How do we know that our standard was uniquely effective or that California midwives abide by its useful guidance? Ca LMs have been practicing under the SCCLM for 8 years, beginning a year before the LMAR started tracking the safety and effectiveness of midwifery care under the LMPA. As measured by the aggregate statistics for maternal-infant outcomes for 2007 to 2013, the relative safety of non-allopathic midwifery equals, and in some categories (Cesarean rates, prematurity, etc) actually exceeds those of mainstream medicine. The care that California licensed midwives to provide in non-medical settings stands on a solid scientific foundation of practitioner competence.

How do we know that our standard was uniquely effective or that California midwives abide by its useful guidance? Ca LMs have been practicing under the SCCLM for 8 years, beginning a year before the LMAR started tracking the safety and effectiveness of midwifery care under the LMPA. As measured by the aggregate statistics for maternal-infant outcomes for 2007 to 2013, the relative safety of non-allopathic midwifery equals, and in some categories (Cesarean rates, prematurity, etc) actually exceeds those of mainstream medicine. The care that California licensed midwives to provide in non-medical settings stands on a solid scientific foundation of practitioner competence.

Another measure of the quality of midwifery practice under the SCCLM is the extremely low number of disciplinary actions against LMs. Using the most recent data (fiscal years 2011-2012 & 20112-2013) the Medical Board only pursued administrative or criminal cases against two midwives during the last 24-months. Based on the total number of midwives licensed during this period, this is a prosecution rate of only 0.003.

Obviously, the Standard of Care for California Licensed Midwives, which included a midwifery code-of-ethics and fourteen pages of practice guidelines, was a success. Nonetheless, the same Standard of Care was summarily replaced by AB 1308 by a single sentence that requires midwives to:

“immediately refer or transfer… if at any point a client’s condition deviates from normal”

According to the language of AB 1308, a midwife’s license may be suspended or revoked for, among other things, failing to consult with a physician and surgeon, refer a client to a physician and surgeon, or transfer a client to a hospital if the woman has a post-date pregnancy and any condition identified in regulations (currently pending) deemed “likely to affect pregnancy or childbirth”.

Violating any provision of the LMPA is deemed to be a crime.

As of this writing (December 2014), the truly independent practice of midwifery does not yet exist. The ability of licensed midwives to provide individualized care based on “best practices” continues to be distorted and diminished by the overarching influence of organized medicine and its well-funded special interest lobbies.

As of this writing (December 2014), the truly independent practice of midwifery does not yet exist. The ability of licensed midwives to provide individualized care based on “best practices” continues to be distorted and diminished by the overarching influence of organized medicine and its well-funded special interest lobbies.

There are only two options here – door #1 or door #2.

What’s behind Door #1?

Since turn-about is fair play, the first is for organized medicine to invite “organized” midwifery as a non-allopathic discipline to sponsor legislation amending the allopathic practice of medicine.

Personally, I’d recommend a new law requiring allopathic medical schools to include courses on the non-allopathic principles and technical skills of physiological management, and as well as the development of policies, protocols, and education of hospital staff to help reduce our 33% CS rate.

I’d want to pass a “full disclosure” law requiring obstetricians to provide scientifically valid and unbiased information about the medical side-effects and complications that accompany the use of obstetrical intervention and invasive procedures. These include induction of labor, use of Pitocin to speed up labor, routine use of continuous of EFM, episiotomy, Cesarean surgery (13-fold increase in emergency hysterectomy, 6% increase in secondary infertility) and the unique dangers to mothers from abnormal placental implantation associated with repeat Cesareans (7% maternal mortality rate for women with placenta percreta).

The new ‘informed disclosure’ law should also require that obstetricians informed pregnant patients about the modern history maternal mortality rate in the US. After a hundred years of steady improvement, the MMR became stagnant in 1982 at 8 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births and remained at that level until 1996. Then the MMR began to steadily increase until it reached 17 deaths per 100,000 a couple of years ago. While it the MMR for the last year published (2012) has decreased to approximately 12 deaths per 100,000, the US rate 39th worldwide, making it safer for mothers to give birth in Bosnia that California.

The rising MMR in the US over the 18 years tracks with the increasing CS rate in the US. A large proportion of the increased maternal deaths are directly or indirectly associated with intra-operative, post-operative, delayed and downstream complications of Cesarean surgery. These categories include hemorrhage, pulmonary embolisms, infection and deep-vein thrombosis (blood clots), anesthetic accidents, bowel obstruction, and other iatrogenic complications. Even elective and repeat C-sections where the pregnant woman was healthy and there were no prior medical complications result in several maternal deaths each year.

The Better Option ~Door #2

The other and I think a more sensible option is that ACOG applies its own advice about respecting the autonomous decisions of women by expanding these principles to the practice of midwifery. ACOG Committee Opinion #214 states that: “Abiding by the patient’s autonomous decision will provide the best care for the pregnant woman and the fetus in most circumstances.”

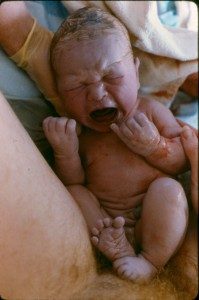

Ina May Gaskin, LM, author of Spiritual Midwifery, leader of direct-entry midwifery in North America, with one of her own home-born babies

This also applies to midwifery. As female midwives, we ourselves are childbearing women and/or daughters, sisters, mothers, and grandmothers to childbearing women. For midwives, there is no “bright line” distinction between us as women providing a professional service, and us as women who are pregnant or giving birth. Put in the words of ACOG’s committee opinions, we are personally “wronged and may be harmed …. physically, psychologically or spiritually” when our autonomy as childbearing women or as midwives are ignored, disrespected, or trampled on.

ACOG already acknowledges: “There may be other social costs associated with this violation of individual liberty“. There is no “maybe” about it — violations of liberty are harmful, individually and to society.

The cost is a “subsequent loss of trust in the healthcare system” that reduces our ability as healthcare providers to help women who have been harmed in the past by violations of their autonomy, which in turn “deter(s) others from seeking care“.

The most harmful aspect of this gender-related violation of trust is that it often prevents women, as mothers and as midwives, from seeking or respecting the opinions of obstetricians. In this case, a significant number of women who can’t get midwifery care due to restrictions imposed by AB 1308 will have unattended births. Unattended childbirth in women who didn’t receive regular prenatal care results in a 20 to 40-fold increase in neonatal mortality, so obviously denying access to midwifery care is not a ‘safety’ measure.

Any “violation of individual liberty” has a negative rebound effect on society, which is the polar opposite of what is needed.

I’d like to end by telling a story about Eleanor Roosevelt during the time her husband was in the White House. I think it perfectly characterizes the virtuous goals of maternity care. A reporter once asked Mrs. Roosevelt who she put first, her husband as president of the United States, or her children. She replied:

“Together with my husband, we put the children first.”

Midwives and obstetricians need to develop trust, mutual respect and the ability to cooperate so that together we can put childbearing women first.

Update ~ 2015 ~ on two new amendments to the LMPA passed in the last year

Update ~ 2015 ~ on two new amendments to the LMPA passed in the last year

https://tinyurl.com/y9f2zwgr

Recommended reading:

- The Art and Science of Midwifery in California (3-part series)

- The Five most important dangers in childbearing

- The Physiological Management of Normal Childbirth: Why American hospitals are unable to provide such care

- The Obstetrical Standard of Care in the US – Historically Illogical, Fundamentally flawed

Links to other historical topics on midwifery and medicine

A companion document on the Healing Arts ~ a peek at the history of the modern-day Medical Practice Act:

A very comprehensive history Remarks by Physicians about midwives & midwifery ~ 1820 to 2014

Addendum #1 Statistical Facts about the Safety of Childbirth ~ what everybody needs to know in order to make sense of the “midwife problem” and why would anyone seek out “alternatives” childbirth services when obstetrics appears to be the obviously safer and superior choice?

Addendum #2 The Safe Childbirth Practice ~ the Difference btw Obstetrics & Physiologically-based Care

http://californiawatch.org/dailyreport/death-rate-childbirth-rises-california-10038