Historical overview

For centuries obstetrics was simply a general part of medicine. Since it did not include any advanced training in reproductive surgery, the skills of the average family practice doctor were not all that different from the typical practice of midwifery. In colonial American, childbirth services were split 50-50 between midwives and MDs. Before the late 19th century, a doctor who attended births used to be called a “man-midwife”. If one of his patients needed a cesarean, he had to call in a gynecological surgeon.

But in the late 1800s Dr. J. Whitridge Williams, himself a gynecological surgeon and also professor of obstetrics at Johns Hopkins University Hospital, insisted that the discipline of obstetrics should actually be a surgical (rather than medical) specialty. At the time, there was a highly contentious rivalry going on between the discipline of obstetrics and gynecology. In discussing this professional conflict Dr. Williams commented that:

“ … gynecology and obstetrics are too sharply divided and are conducted upon too practical a basis to give ideal results.

The progressive gynecologist considers that obstetrics should include only the conduct of normal labor, or at most .. cases that can be terminated without radical operative interference, while all other conditions should be treated by [the gynecologist] – in other words, that the [work] of the obstetrician should be [limited to] that of the man-midwife.”

To eliminate detrimental rivalry and economic completion and better promote the interests of both disciplines, it was decided that the two professions join forces to form a single combined surgical specialty referred to as “ob-gyn”. Dr. Williams was the perfect choice to arrange the forced marriage between these rival groups. His first position after graduating from medical school was to set up the gynecological surgery departmentin 1893 for the new Johns Hopkins University Hospital. Still employed by Johns Hopkins, Dr. Williams was appointed as associate professor of gynecology a year later and served a two-year term as vice-president of the American Gynecological Society in 1903-04.

After being promoted to chief of obstetrics at Johns Hopkins, Dr. Williams wrote his classic obstetrical textbook “Williams Obstetrics”, first published in 1903. By the times he was appointed Dean of the School of Medicine in 1911, the medical speciality of obstetrics and surgical speciality of gynecology had been providing care as the hybrid surgical specialty of obstetrics and gynecology for more than a decade. The historical process for providing childbirth services as a cooperative venture between women and their family doctors or midwives was unilaterally phased out, as modern medicine’s latest speciality — obstetrics and gynecology — was advanced as the safer and more modern way to have a baby.

Between 1900 and 1910 the traditional practice of obstetrics, which had focused on the individualized needs of each childbearing woman, was dramatically (some might say drastically) re-congiured. The classical philosophy of ‘respectful restraint’ (i.e. Mother Nature knows best) was replaced by an unbridled enthusiastic for new ideas and new ways of thinking.

This included a very negative definition of female reproductive biology that saw childbearing women as the helpless victims of an inherently defective, even pathological process of so-called ‘normal’ childbirth. Physicians who aggressively intervened were seen as cutting-edge leaders. Newspapers reported that normal pregnancy was now considered to be a “nine month disease requiring a surgical cure“.

From this perspective, only benefit was to come from interventions that shortened the length of labor. This particularly applied to surgical procedures that reduced the ‘exposure’ of the fragile fetal skull to the potentially harmful maternal pushing efforts of 2nd stage labor. To protect the mother’s delicate vaginal and perineal tissues from being damaged by the baby’s hard and relentlessly advancing head, the routine use of episiotomy and forceps were recommended. Official concern for the mother’s perineum was best characterized by a famous 20th century obstetrician. He described spontaneous birth to be about “as natural as falling on a pitchfork”!

Obstetrical management and surgical delivery as the standard of care for normal childbirth represents the most profound change in childbirth practices in the history of the human species.

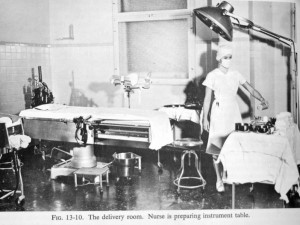

Labor was a heavily medicalized process under the care of hospital nurses. Newly hospitalized women were immediately given powerful injections of narcotics and the Twilight Sleep drug scopolamine. The purpose of Twilight Sleep was to produced amnesia, but scopolamine also was an hallucinogenic. Over the many hours of labor, women received multiple doses of both drugs and could not remember anything that happened while under their influence. When women began to push, they were moved by stretcher to the ‘delivery’ room, which was essentially an obstetrical operating room.

Newly hospitalized women were immediately given powerful injections of narcotics and the Twilight Sleep drug scopolamine. The purpose of Twilight Sleep was to produced amnesia, but scopolamine also was an hallucinogenic. Over the many hours of labor, women received multiple doses of both drugs and could not remember anything that happened while under their influence. When women began to push, they were moved by stretcher to the ‘delivery’ room, which was essentially an obstetrical operating room.

The conduct of normal vaginal birth by ob-gyn specialists was considered to be a new surgical procedure called “the delivery”. Like other kinds of operations, it required that the patient be anesthetized.

Dr. Williams was very proud to announce in 1912 that:

“in Johns Hopkins Hospital no patient is conscious when she is delivered of a child. She is oblivious, under the influence of chloroform or ether.” [Twilight Sleep: Simple Discoveries in painless childbirth” p. 67]

The new surgical standard for normal birth included general anesthesia, episiotomy, delivery of the baby with forceps, manual removal of the placenta, and suturing of the perineal incision.

The new surgical standard for normal birth included general anesthesia, episiotomy, delivery of the baby with forceps, manual removal of the placenta, and suturing of the perineal incision.

This was followed by a mandatory separation of mother and baby for the first 12 hours as L&D nurses watched while the mother recovered from anesthesia, and nursery nurses monitored the new baby. Between the amnesic drugs received during labor and being rendered unconscious during the birth, many women described a bizarre and disturbing feeling of “blankness” where their experience of the birth of their baby should have been.

Unfortunately, these obstetrical protocols were all non-negotiable. As standard fare in every hospital, the laboring woman could not decline any procedure or drug, or any have any say whatsoever as to what was (or wasn’t) done to her. Even if a new mother remembered being mistreated or having an unexplained complication, no one would believe her, after all she’d been medicated with narcotics and hallucinogenic drugs and could never be a creditably witness on own behalf. This was important, as no husbands or other family member were ever allowed behind the swinging double doors to the labor ward that declared in big black letters: “Authorized Personnel Only”.

But the most important issue was how mothers and babies were being systematically harmed by these heavily medicalized obstetrical routines. Childbirth-related deaths of American mothers in the 1930s were orders-of-magnitude higher than maternal mortality rates (MMR) for Sweden and other European countries at the turn of the previous century (1900). Neither the narcotized labor patient nor the general public understood how risky these medical interventions and invasive procedures were when used routinely on a healthy population. Known side-effects and drug reactions from one intervention often required the use of more invasive procedures that resulted in a cascade of complications and sometimes ended in a preventable death for mother or baby.

Twilight Sleep drugs triggered a near psychotic-break in many laboring women. To keep such women from crawling out of bed, falling, attacking other patients or biting the nurses, heavy leather restraints were used tie them down on their back to the four corners of the bed frame. Unfortunately, keeping a mother-to-be flat on her back throughout the entire labor was the most painful position for her and also inferred with blood flow to the placenta, which causes fetal hypoxia (i.e. oxygen deprivation).

The use of forceps often damaged the mother’s pelvic structures. One particularly awful complication was an ‘obstetrical fistula’ — an abnormal opening between a new mother’s vagina and either her bladder or rectum that left her permanently incontinent of urine or stool. Before modern surgical repairs, this sentenced these new mothers to life as a social outcast.

The use of forceps often caused neurological damage to the baby. Narcotics from the laboring mother’s blood stream that transferred to the unborn baby during labor often prevented the baby from breathing after it was born. As an L&D nurse during the late 1960s, I witnessed narcotic-related fatal respiratory depression caused the death of many otherwise healthy newborns. As late as 1960, the general anesthesia routinely given to mothers during delivery was listed as the third most frequent cause of maternal death.

While the obstetrical profession continue to ascribe to “more is better”, the conclusions of the 1931 White House Conference on Child Health and Protection were just the opposite. In a report published in 1932 (Reed), the care of midwives was specifically praised because they refrained from interfering in the normal biology of childbirth:

“. . .that trained midwives surpass the record of physicians in normal deliveries has been ascribed to several factors. Chief . . . is the fact that the circumstances of modern practice induce many physicians to employ procedures which are calculated to hasten delivery, but which sometimes result in harm to mother and child. On her part, the midwife is not permitted to and does not employ such procedures. She waits patiently and lets nature take its course.” (emphasis in original)

The book “Death in Childbirth: An International Study of Maternal Care and Maternal Mortality, 1800–1950“ [Irvine Loudon; 1992] reported that:

“the risk of dying in childbirth in 1863 and 1934 were virtually identical. The high death rate was the result of lax antiseptic practices and poorly trained [physician] birth attendants who engaged in unnecessary and dangerous obstetrical interventions, especially forceps deliveries.

This fact became evident when national differences were taken into account. Loudon found that in 1935 the rate of obstetrical interference in Holland was 1% and in New York 20%. When interference occurred, the death rate due to sepsis (infection) was 40 per 10,000 births, while the rate for spontaneous deliveries was 4 per 10,000.”

By the 1950s some L&D nurses began to criticize the obstetrical interventions being used routinely across the country as dangerous and contributing to other abusive practices, such as tying women to their beds and slapping them if they became upset. A few of these nurses were willing to provide whistle-blower information to popular women’s magazine.

The Ladies’ Home Journal kicked things into high gear in 1958 with an article called called “Cruelty in Maternity Wards“. Their account of the “tortures that go on in modern delivery rooms” triggered a flood of stories by other women who claimed: “The whole thing is a horrible nightmare”. A nurse from Canada wrote: “I’ve seen patients with no skin on their wrists from fighting the straps.” A woman from Detroit thought the answer was to “… let a few husbands in the delivery rooms and let them watch what goes on there. That’s all it will take — they’ll change it!”

The obstetrical profession’s reaction to this public outcry was simply to stonewall. Obstetricians insisted that lay people just didn’t ‘understand’ and were misinterpreting events recounted by mothers and L&D nurses. Representatives of the ob-gyn lobby focused on women’s magazines in general – what hubris for a magazine reporter claim to know more than a specialist in the field of obstetrics?

However, there was always a small minority of women who gave birth quickly, before they could be medicated with Twilight Sleep drugs and had vivid and intact memories of disturbing treatment. L&D nurses never got any of those “happy pills”, so nothing was wrong with their memories either. When these women were collectively asked: “Who are you going to believe? us and our obstetrical lobbyists, or your own lying eyes?” the two-fold answer was simple enough:

{1) the routine use of obstetrical intervention in healthy women during normal labor and birth was neither harmless nor helpful as the ob-gyn profession had always insisted

{2} obstetricians as a class preferred to remain clueless to these problems

From many different perspectives the inescapable conclusion was that contemporary obstetrics as an “expert” system was failing society in the very area it was supposed to have the most mastery and expertise – that is, preserving the health of already healthy mothers and babies.

Part 3 –Turning a backlash into effective political action

Reference: Obstetrics and Midwifery ~ Antiquity and the Medieval and Early Modern Period http://www.faqs.org/childhood/Me-Pa/Obstetrics-and-Midwifery.html

Loudon, Irvine. 1992. Death in Childbirth: An International Study of Maternal Care and Maternal Mortality, 1800–1950. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

What a Blessing She Had Chloroform: The Medical and Social Response to the Pain of Childbirth from 1800 to the Present – Donald Caton, M.D.

Birth Day: A Pediatrician Explores the Science, the History, and the Wonder of Childbirth – Mark Sloan, M.D.

Deliver Me From Pain: Anesthesia & Birth in America – Jacqueline Wolf