tinyurl.com/ybvde6cx

Safe, cost-effective Childbirth in the 21st Century

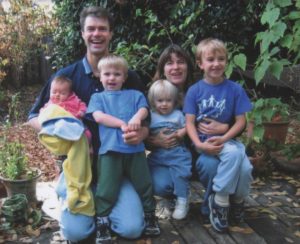

Healthy childbearing women and their babies are always safer when the mother-to-be receives regular prenatal care during pregnancy, is cared for by a trained and experienced birth attendant throughout active labor, the birth of her baby, the immediate postpartum-neonatal period and initial breastfeeding and that both new mother and new baby receive appropriate follow-up care for at least six weeks after the birth.

That’s exactly what California Licenced Midwives are trained, licensed, equipped to do.

The California Licensed Midwifery Practice Act of 1993 (LMPA)

The Licensed Midwifery Practice Act was passed unanimously by the California Legislature in 1993. Since then, approximately 50,000 families in California have had a professional midwife-attended spontaneous vaginal birth in out-of-hospital locations.

Every year more than 4,000 healthy pregnant women in our State seek alternative forms of maternity care from licensed midwives. In 2016, more than 3,000 babies were born in a non-medical setting (birth centers and family residence) under the care of California Licensed Midwives.

The best description of the role of professional midwives is to characterize them as “educated observers with emergency response capacity“. We watch, look and listen for a living, sitting quietly on the sidelines but always ready and able to spring into action, if or when the need arises.

Complications, while infrequent, can occur in any pregnancy or labor, no matter how healthy the mother or normal the pregnancy. For this reason, professional midwifery care always includes timely access to and appropriate use of medical services as an integral part of physiologically-based midwifery care, to be called on when needed to treat complications or if requested by the mother.

Should an unexpected medical problem occur during pregnancy or childbirth, midwives are trained as first-responders, able to provide effective emergency interventions, and when necessary, refer or transfer, or arrange rapid transport of mother or baby to appropriate medical services.

This greatly reduces risks during pregnancy, and the frequency and severity of preventable childbirth complications, making normal childbirth in healthy women both safer and more cost-effective. Midwives also provide emotional and social support for new parents in the months preceding and following the birth.

For women who received maternity cared from Ca LMs between 2007 and 2016, the incidence of prematurity was under 2% **. In the U.S. as a whole, preterm and premature births occur in about 12% of pregnancies and this is one of the top causes of infant death in this country.

For women who gave birth under the care of Ca LMs during those same years, the incidence of Cesarean delivery is less than 10%**, while the US rate is 32% — a three-fold higher rate that is associated with increased infant morbidity and maternal mortality.

For women who gave birth under the care of Ca LMs during those same years, the incidence of Cesarean delivery is less than 10%**, while the US rate is 32% — a three-fold higher rate that is associated with increased infant morbidity and maternal mortality.

**Licensed Midwives Annual Report (LMAR-2007-2016).

Since 49% of the cost for all hospital births in California are reimbursed by the state-federal MediCal program, much lower rates of prematurity and surgical delivery associated with the professional services of licensed midwives save taxpayers many millions of dollars every year.

Why most Families Choose Out-of-Hospital Birth

The reasons women frequently give for choosing an OOH location for normal childbirth are:

- cultural traditions

- strongly-held religious beliefs

- economic issues

- personal preference

These reasons are relatively self-explanatory, so I won’t belabor the point. However, there are other important, but not well-known or understood reasons that I’d like to explain in some detail.

Childbirth in Women with PTSD

When midwives ask potential clients why they are interested in community-based midwifery care, a significant number of women say their reason for choosing OOH birth is in reaction to a prior traumatic experience. Women who experienced childhood physical or sexual abuse, or were the victim of a violent crime or sexual assault as adults (including “date-rape”), are naturally distrustful, even fearful, and often develop a very rational fear of being overpowered.

As a result, these women live with a pervasive level of anxiety about their ability to protect their bodily integrity. They purposefully avoid situations that entail disparities in social status or power between themselves and other ‘powerful’ individuals or groups. They also avoid intimidating situations, such as being required to lay on their backs in physically vulnerable positions, which is a necessary aspect of gynecological exams and other invasive medical procedures. These and similar incidents often trigger symptoms of PTSD including flash-backs and disassociating from their emotions or surroundings.

A small proportion of women with this debilitating form of PTSD either avoid pregnancy altogether or schedule an elective Cesarean. It’s the woman’s way of circumventing what she sees as the indignity of invasive vaginal exams during labor and other medical procedures. Hospital protocols being what they are, she doesn’t believe that her physical and emotional privacy will be adequately protected. Scheduling a surgical delivery also eliminates her fear of a loss of control and bodily integrity during a normal vaginal birth in an environment that she often sees as a quasi-public venue.

Fortunately, the majority of previously traumatized women are able to tolerate and even welcome pregnancy. A significant proportion these brave souls cope with their ‘special circumstance’ (PTSD) by seeking out community-based midwifery care. Assuming the mother remains healthy, the pregnancy is normal, and her labor progresses normally, these women plan to have a midwife-attended home birth or to give birth in free-standing birth center staffed by midwives and, in some places, family practice physicians.

The Intimidating Aspects of Hospitals and Hospitalization

The Intimidating Aspects of Hospitals and Hospitalization

Such women often describe a traumatic experience as a child with an illness or injury that required them to be hospitalized and abruptly separated from their family for weeks or months. Their care many have included isolation due to a serious infection, or 2nd and 3rd-degree burns with painful or distressing treatments. Sometimes the traumatic hospital experience happened as an adult and involved a serious accident of a family member or the prolonged hospitalization of an elderly or terminally-ill relative.

For the lay public (which is 99% of us), hospitals are intrinsically intimidating places. Doctors often hold our lives or those of our loved ones in their hands, but frankly, they are also busy ‘important’ people who can be brisk and off-putting.

For the lay public (which is 99% of us), hospitals are intrinsically intimidating places. Doctors often hold our lives or those of our loved ones in their hands, but frankly, they are also busy ‘important’ people who can be brisk and off-putting. Historically, the authoritarian nature of the medical culture always made the doctor/not-a-doctor relationship intrinsically intimidating. While its much better today than a hundred years ago, the universally perceived power-disparity between medical doctors and the rest of us is still operative. We are afraid of ‘wasting the doctor’s time’ or making a fool of ourselves, which interferes with our ability to ask important questions or to risk taking up the doctor’s time to fully discuss treatment options.

For hospital patients, these factors represent a double whammy. To be a patient is to also be in pain, afraid, sick as a dog, intimidated by high-tech medical equipment, and laying nearly naked on an ER stretcher waiting to be admitted to a hospital bed while wretching into a bowl or using a bedpan with only a flimsy curtain for ‘privacy’, thus being both helpless AND vulnerable to forces beyond our control or ability to understand.

Nothing about this is a level playing field when it comes to social interaction between patients and the hospital staff and the practical necessity to engage an egalitarian decision-making process when we are, in fact, in a subservient role.

If the laboring woman also felt that her needs, as she experienced and expressed them, were ignored or otherwise not taken seriously, or she was pressured to have interventions she didn’t want and didn’t believe necessary, it often results in a profound loss of confidence in the current system.

Families seek out midwifery care specifically to avoid the highly medicalized management of normal childbirth in the US, which they experience as similar to trying to give birth in a busy ICU.

Women in the thors of labor experience themselves as tethered to the bed by IV lines, an automatic blood pressure cuff on one arm, a pulse oximeter on a finger of the other hand, two EFM belts around their pregnant belly, with cords leading back to the electronic fetal monitor standing next to their bed, as the mother-to-be lies on her backs, watching unfamiliar members of the hospital staff come and go, while the rest of their family stands out in the hallway, waiting for the baby to be born.

The good news is that Legislative Intent of California Licensed Midwifery Practice Act perfectly matches the needs of these families for a safe and legal ‘alternative’ to a routinely medicalized hospital care and since 1993, has made this risk-reducing form of available to many thousands of California families.

SB 350 was also designed to prevent the many serious problems for childbearing women (and ultimately for society) that are associated with the category of ‘no care’, including an increase in premature births and the dangers of unattended births when state-regulated professional midwifery care is not available.

Tell California Legislators to Vote for Stepping Stones, not Stumbling Blocks

Tell California Legislators to Vote for Stepping Stones, not Stumbling Blocks

There is no justification for any amendment to the LMPA (such as AB 1308) that consciously puts stumbling blocks in the path of healthy childbearing families and uses subterfuge to deny care to the very women who most need access to this traditional form of maternity care. Community-based midwifery provides a safe and acceptable alternative to highly medicalized and expensive hospital care. Senator Killea to introduced SB 350 (the LMPA) in 1993 specifically to provide access to professional midwifery by self-selected women and their families that deserved to have unwanted and highly medical hospital-based care AND to do so safely by having access to quality maternity services from professionally-trained and state-regulated direct-entry midwives.

Annulment of Midwife’s Scope of Practice and Veto Power over CB woman’s right to self-determination

In 2013, lobbyists for a special interest group — the surgical specialty of obstetrics and gynecology — approached a California legislator with what must have seemed like a logical argument for amending the LMPA. They asked for legislative provisions that:

- nullified the original scope of practice for licensed midwives

- repealed the Standard of Care for California Licensed Midwives (SCCLM)

Gateway Claims by Special Interest Groups are Neither Accurate or Objective

AB 1308 usurped the legitimate gateways keepers to midwifery care (i.e. professional midwives) by inserting legal language into the LMPA that identified the obstetrical profession as controlling the ‘gateways’ to maternity care as provided by California licensed midwives. As a consequence, AB 1308 specifically eliminated the normal constitutional principle of ‘patient autonomy‘ for healthy childbearing women as it applies to women receiving care from California licensed midwives.

This was done by making it illegal for midwives to provide care to pregnant women who had certain risk factors and eliminating the mother-to-be’s right to decide for herself whether she wanted to consult with an obstetrician in relation to these risk factors. Claims that limiting the scope of practice for midwives and eliminating Patients Rights for their pregnant women clients would make childbearing safer was neither accurate or objective.

This was done by making it illegal for midwives to provide care to pregnant women who had certain risk factors and eliminating the mother-to-be’s right to decide for herself whether she wanted to consult with an obstetrician in relation to these risk factors. Claims that limiting the scope of practice for midwives and eliminating Patients Rights for their pregnant women clients would make childbearing safer was neither accurate or objective.

As you continue to read, it will become clear that organized medicine was and remains more focused on the economic interests of the surgical specialty they represent than the well-being of healthy childbearing women who did not want or need or voluntarily consent to routine obstetrical.

The Scientific Art of Midwifery, its History, and its Future

The traditional role of midwives is that of:

“an educated observer with emergency response capacity”.

The midwife’s primary duty is to safeguard the normal physiological process while monitoring the well-being of mother and unborn baby. Midwives respond as the need arises, always being careful not to unnecessarily disturb or interfere with the normal biology of spontaneous childbirth as long as things are progressing normally.

This ‘eyes-on, hands-off’ quality of care describes a professionally-educated and clinically-experienced midwife who is physically present during active labor and able to watch and listen carefully and respond appropriately as the need arises.

This defines physiologically-based care as provided to healthy women with normal term pregnancies. The family’s informed decision to labor in a non-medical setting (parents’ home or free-standing birth center) is based on the use of time-tested physiologic childbirth practices in conjunction with the timely and appropriate use of modern medical science as needed.

Planned OOH birth — An Integration of “Plan A” and “Plan B”

Community-based midwifery care begins with a family’s informed decision to give birth in a community setting (i.e. an out-of-hospital birth) after their midwife has provided relative information about the risks and benefits normal birth in a non-medical setting for healthy women with a normal pregnancy. Midwives describe this formal “plan” as having two aspects or possible outcomes, one involving normal birth at home and the other a transfer of care to hospital-based obstetrical services.

Under the 1993 LMPA and the 2006 Standards of Care for California Licensed Midwives (SCCLM), all midwifery clients must consent, a priori, to the use of emergency medical services and/or hospital transfer for themselves or their newborn in event of a birth-related emergency. Midwives and families both see this as an appropriate safeguard to the immediate and long-term well-being of both mother and her unborn/newborn baby requires, which sometimes requires the use of 21st-century medical science as indicated.

The first part of community-based midwifery care — “Plan A” — refers a spontaneous labor at term (after 37 completed weeks of pregnancy) that progresses normally and a mother and fetus who tolerate the various stages of labor and a normal spontaneous birth at home or in a birth center without incident.

If, for any number of possible reasons, things don’t progress as expected or the parents simply request medicalized care, “Plan B” kicks in. This refers to an intrapartum transfer to a local hospital that provides comprehensive obstetrical services. Once admitted, the mother’s care is legally taken over by an obstetrician and the hospital L&D staff.

However, “Plan B” generally includes the continuing supportive presence of her midwife, who accompanies the family to the hospital and usually remains with the mother throughout the remainder of the labor and birth. After the new mother and baby are discharged, the midwife resumes her role as primary caregiver, providing regular postpartum-neonatal home and office visits for at least 6 weeks.

Some midwives also offer ‘2nd-nine-months care’ by seeing the new mother and her infant again at 3, 6 and 9 months. They provide extended postpartum care and social support for new families. This includes helping the new mother deal with the often stressful family dynamics of integrating a newborn into the household, breastfeeding issues, education about normal child development, as well as informally monitoring the mother for signs of postpartum depression that families often don’t pick-up on.

Historically, the presence of a trained midwife has always made childbirth orders-of-magnitude safer for laboring women and their unborn, newly-delivered mothers and their newborn babies.

However, it is equally true that prior to the development of modern medical science, neither midwives or doctors were reliably able to detect problems early on, before they became serious complications. When such a serious complication occurred during or immediately after childbirth, the medical profession had very little to offer.

But the development of the new biological sciences in the early 20th century made it possible to combine the time-tested methods of physiologic childbirth as provided primarily by midwives with the best advances in obstetrical science, to create (at least in theory) the best of both worlds.

The 20th-century marriage of Traditional Midwifery and Modern Medical Science

The scientific practice of modern medicine, and the incredible ‘medical miracles’ for which it is rightfully famous, originated with the new scientific ability to prevent potentially-fatal bacterial contamination (germs and other pathogens) when performing medical and surgical procedures and to drastically reduce deadly nosocomial (i.e., hospital-acquired) infections from cross-contamination between hospitalized patients themselves and btw patients and the hospital staff.

Before these new scientific discoveries, the bio-hazard nature of hospitals made them extremely dangerous — places to avoid if at all possible — as from 20% to 90% of hospital patients died from post-op infections associated with some surgical procedures.

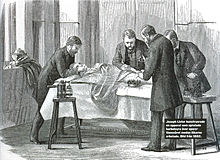

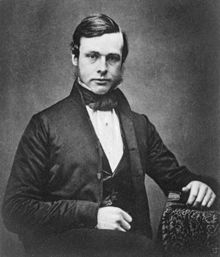

So it’s fitting that modern maternity care also traces its history back to the discovery of the Germ Theory of infectious disease in 1881, and the risk-reduction strategies (principles of antisepsis) developed by the British surgeon to Queen Victoria, Sir Joseph Lister. This consisted of scrupulous hand-washing, isolation of infected patients, using disinfectants and germicides to wash down hospital walls, floors, furniture, and equipment. Of particular importance in the war against bacteria was the sterilization of surgical instruments and the use of strict “sterile technique” during invasive procedures, such as vaginal exams during labor, and operations such as forceps deliveries.

We don’t usually think of the use of forceps and other invasive medical procedures associated with obstetrical care (such as manual removable of a retained placenta) as a ‘surgical operation’ but technically it is. Anytime something from the outside world (gloved hand, forceps, another instrument, a surgical sponge, etc) is introduced into a sterile body cavity, it is a ‘surgical procedure’ and requires the use of surgically ‘sterile’ technique in which everything that touches the patient must be uniformly sterile.

Three cheers for the modern biological sciences & the physician-scientists that brought this about!

Science-based Maternity Care

What we now refer to as “maternity care”, which includes the new invention of prenatal care, wasn’t developed until early in the 20th century.

What we now refer to as “maternity care”, which includes the new invention of prenatal care, wasn’t developed until early in the 20th century.

The purpose of maternity care is to preserve the health of already healthy childbearing women. Mastery in this field means bringing about a good outcome without introducing any unnecessary harm or unproductive expense. In the US, 90% of women who become pregnant every year are healthy and 70% to 80% are still healthy and enjoying a normal healthy pregnancy with a single fetus in a head-down position nine months later.

The ideal maternity care system seeks out the point of balance where the skillful use of physiological management and adroit use of medical interventions if necessary provides the best outcome with the fewest number of medical/surgical procedures and least expense to the healthcare system and lowest rate of iatrogenic and nosocomial complications.

The development of prenatal care in the early 20th century allowed professionally-trained midwives and doctors, for the first time, to routinely risk-screen pregnant women at each antepartum visit. This included lab work to see that the mother-to-be wasn’t dangerously anemic or infected with hepatitis or a sexually-transmitted disease.

The development of prenatal care in the early 20th century allowed professionally-trained midwives and doctors, for the first time, to routinely risk-screen pregnant women at each antepartum visit. This included lab work to see that the mother-to-be wasn’t dangerously anemic or infected with hepatitis or a sexually-transmitted disease.

The pregnant woman’s blood pressure and urine were regularly checked for evidence of pre-eclampsia and diabetes, while the unborn baby’s growth, position, and heart rate were also monitored. This preventative care allowed both doctors and midwives to detect and correct small problems before they became serious complications. Equally important, it helped to identify women with serious medical conditions, such as heart or kidney disease, or high-risk pregnancies so they could be immediately referred to an appropriate specialist.

Quality prenatal care saves the lives of mothers and babies and costs a hundred-fold less than the bills for intensive hospital care and other medical treatments for complications that could have been prevented if the mother had received good prenatal care.

During the 20th century, there has been a steady improvement in maternal-infant outcomes around the world. Many wrongly assume these improved outcomes were was the result of the highly-medicalized care for healthy women in the world’s richest countries, particularly the US.

However, these good outcomes turn out to be the result of an improved standard of living, general access to healthcare and medical services and, in particular, the preventive use of people-intensive, low-tech maternity care.

However, these good outcomes turn out to be the result of an improved standard of living, general access to healthcare and medical services and, in particular, the preventive use of people-intensive, low-tech maternity care.

This describes the prophylactic use of eyes, ears, hands and a knowledge base by maternity care professionals, who are able to screen for risk and refer for medical evaluation as needed.

The best (and smartest!) form of maternity care integrates the principles of physiological management with best advances in obstetrical medicine to create a single, evidence-based standard for all healthy women with normal pregnancies, with obstetric interventions reserved for those with complications or if requested by the mother

This is the best ‘medicine’ for normalizing childbirth in a healthy population. @last edit 03-12-2018@

Continue to Part Two ~ The Art & Science of Modern Midwifery in California

Associated Topic –> The Physiological Manage of Normal Childbirth in Healthy Women ~ What, how, and why it’s usually not provided in hospital obstetrical departments